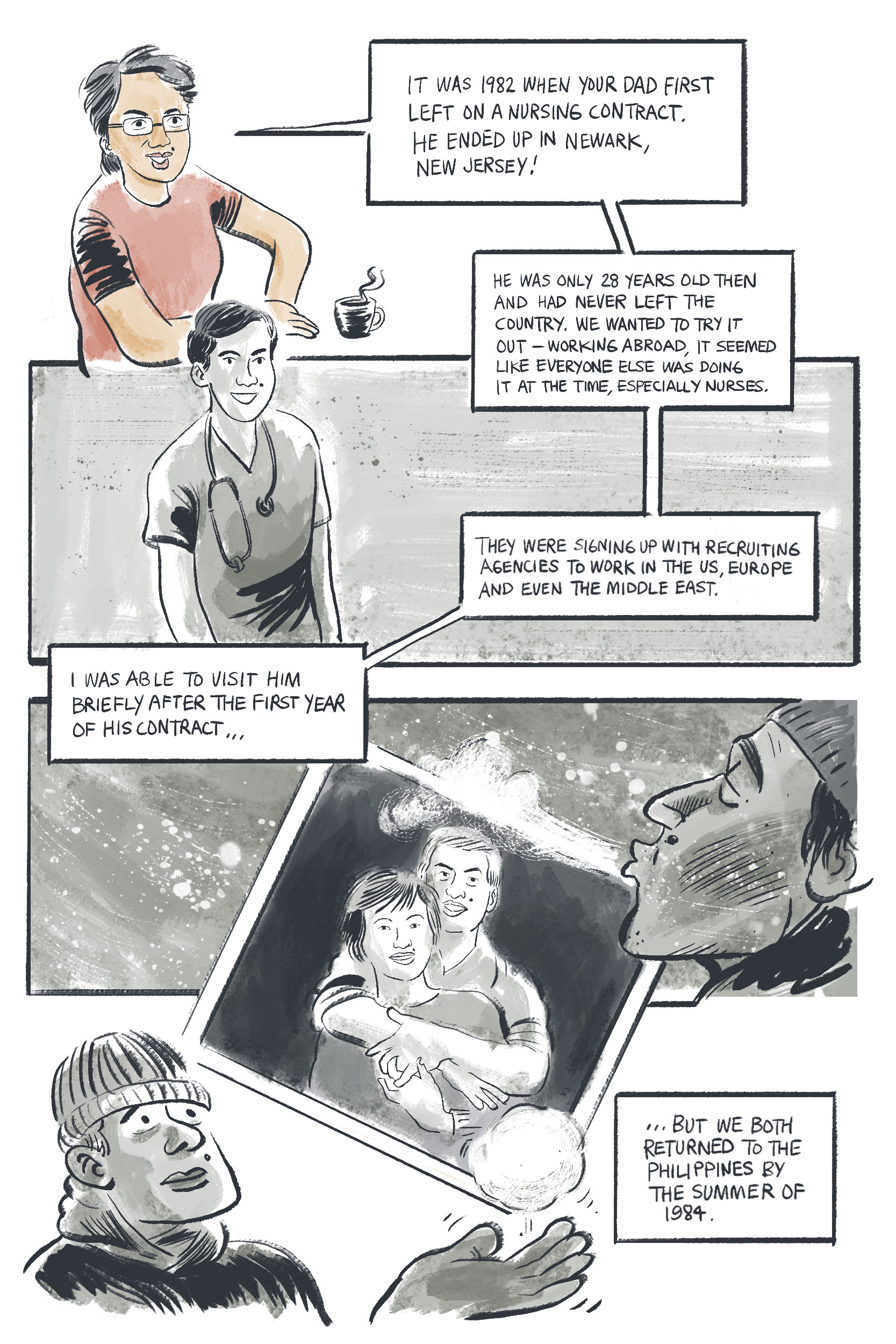

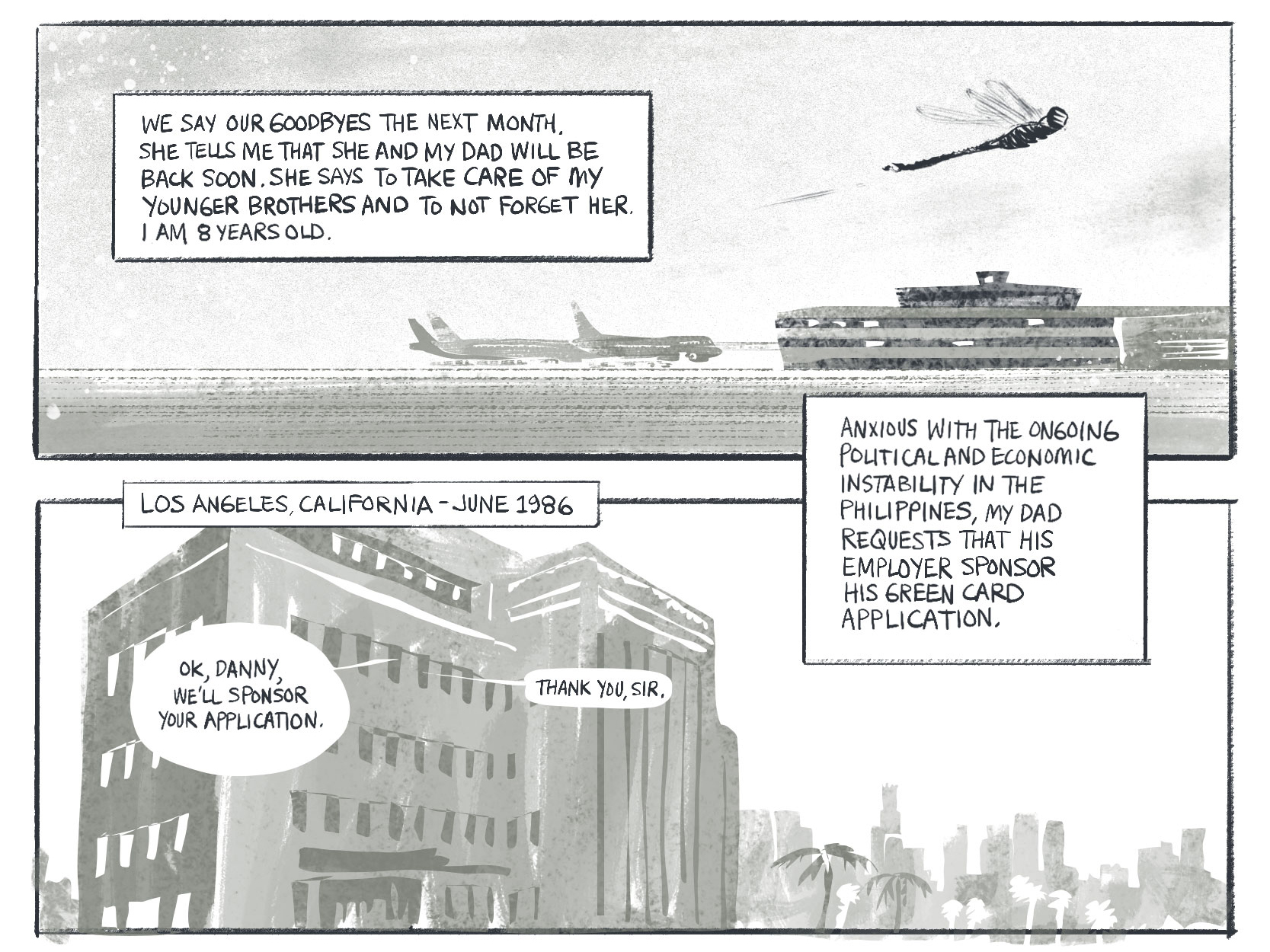

My dad, Danilo, got a contract at White Memorial Hospital in Los Angeles, California just after my brother Chris was born. My two younger brothers and I didn't see him again for almost 10 years.

During the school year, we lived in a small, two-bedroom apartment in Quezon City in Metro Manila, sharing the space with my uncle, an accountant for an American company, and two aunts, a librarian and a nursing student.

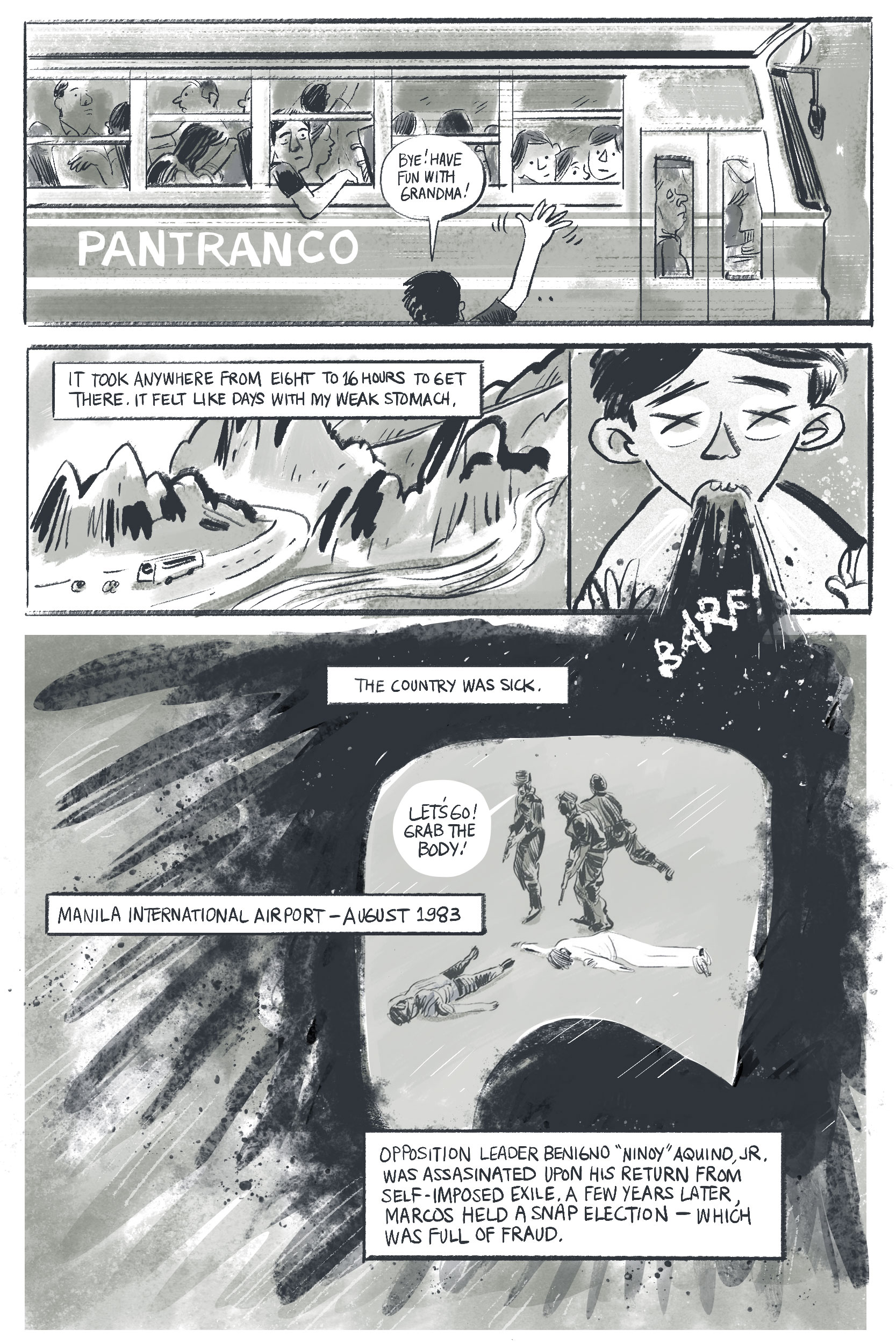

In the summer, they shipped my brothers and I to my grandparents’ home in the rural province of Isabela.

It was a long bus trip north, traversing almost 400 miles of a two-lane highway that carved through rice valleys and the mountainous Cordillera region, home to many indigenous groups in Luzon, the Philippines’ northern island.

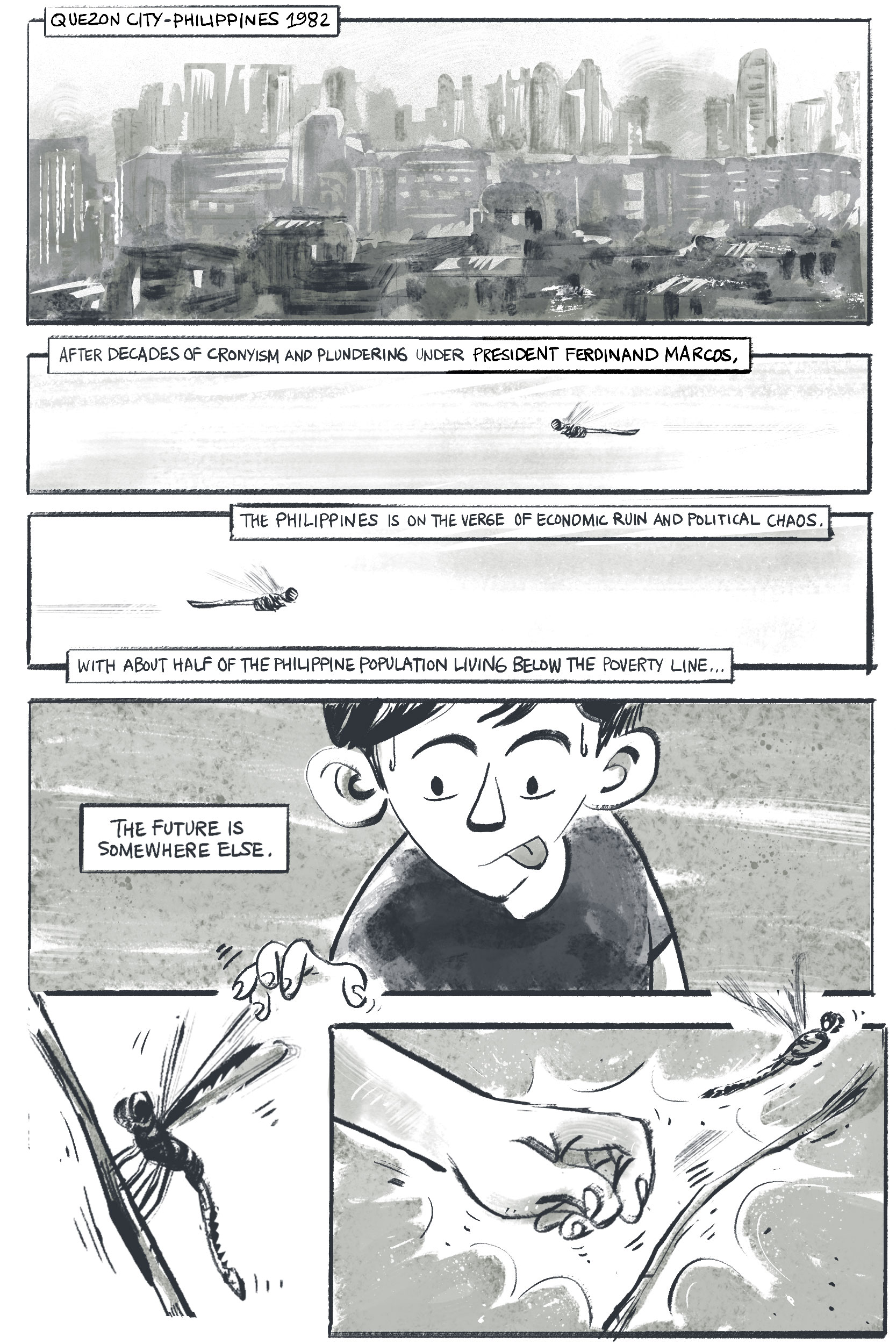

Under Marcos’ rule, the Philippine military committed human rights atrocities and some of those who opposed the government were tortured or killed, or simply disappeared.

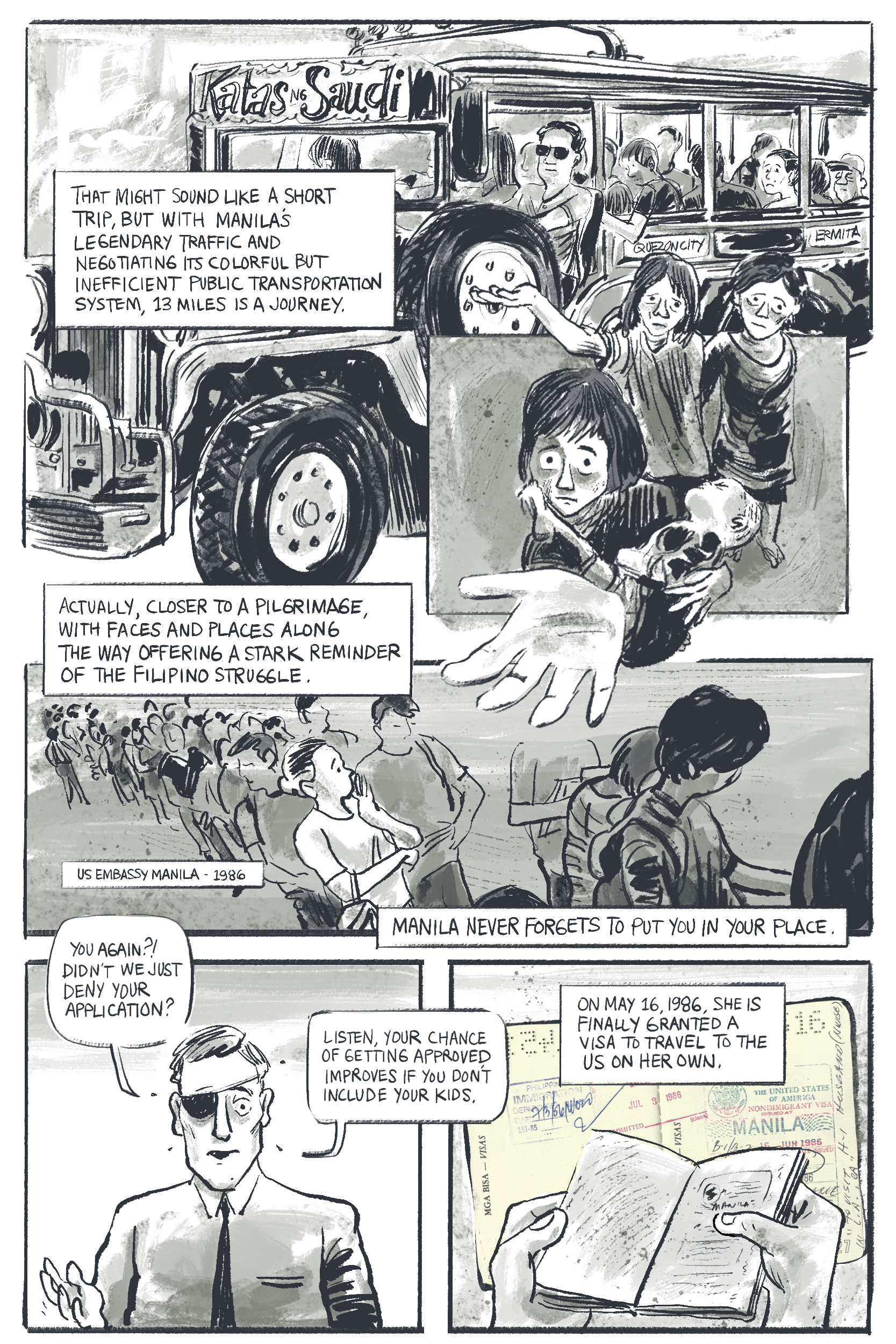

My mom, Josie, applied numerous times for tourist visas for the whole family that spring. Each time she went to the US Embassy, it was an all-day event that began with a 13 mile-long commute from Quezon City to Manila.

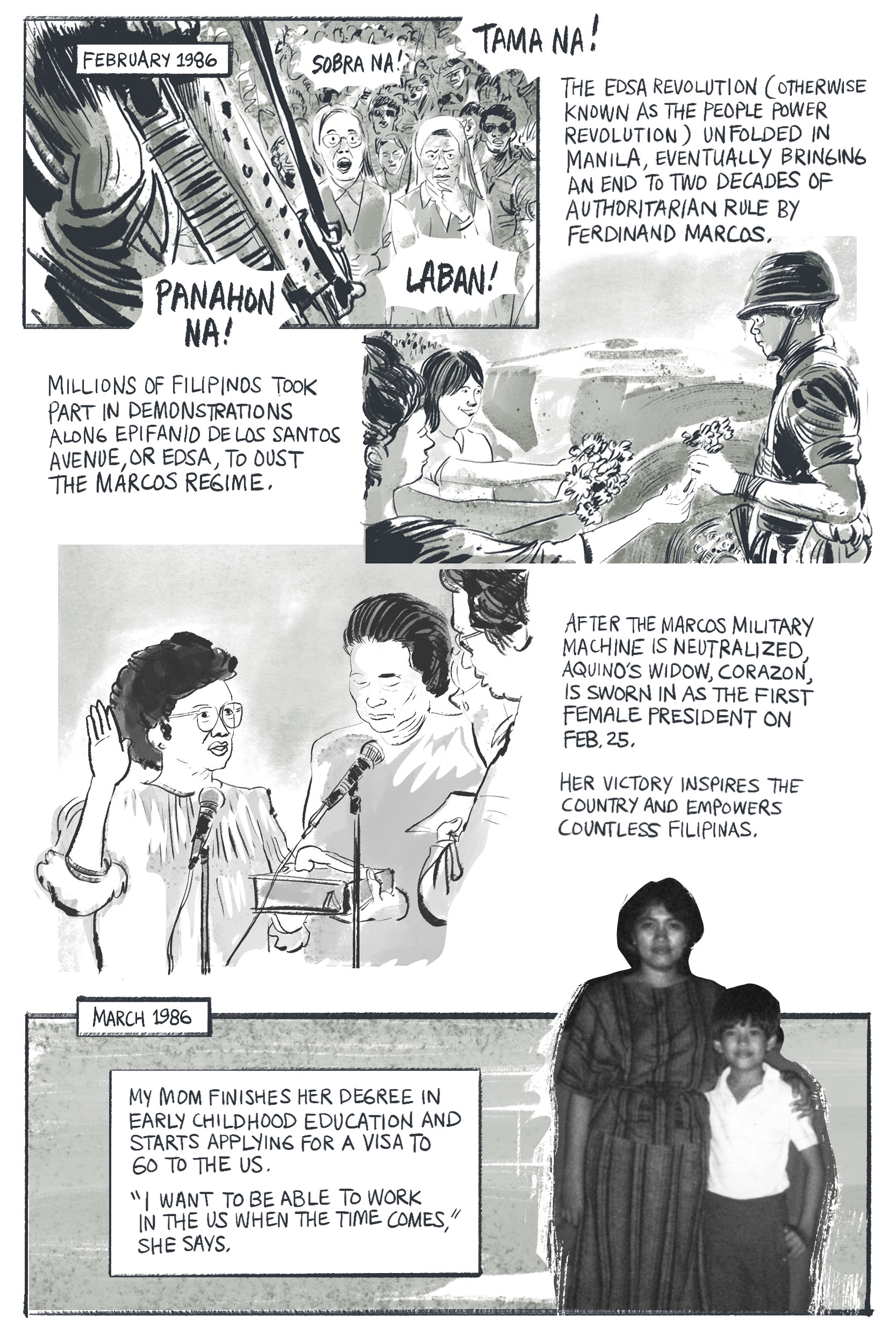

The new Aquino administration was a national symbol of reform, but the administration struggled to address the country’s worsening economic problems while enduring numerous coup attempts from forces loyal to the ousted regime.

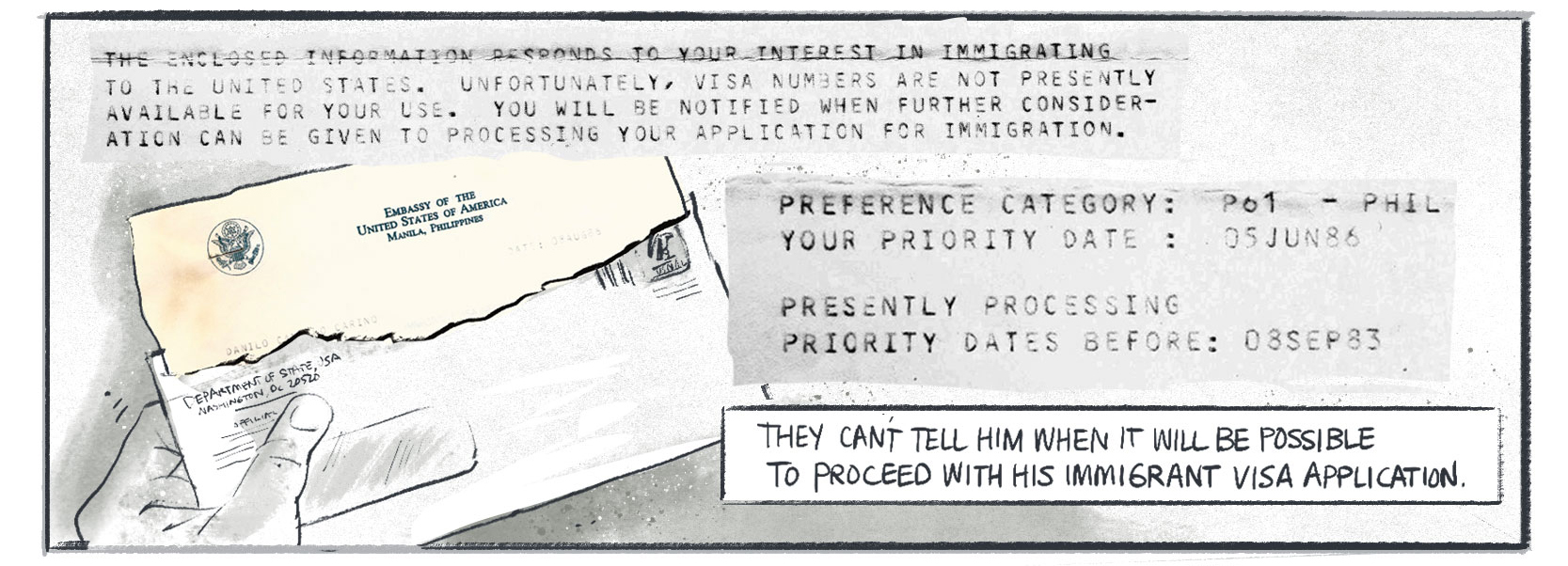

In June 1986, the hospital agreed to sponsor my dad. They filed I-140 and I-485 forms, so that he could become a lawful permanent resident.

On Aug. 8, 1986, he received a letter from the US Embassy in Manila notifying him that his application priority date is June 5, 1986 — that’s the date his application was officially filed. But the embassy said they’re still processing applications submitted on or before Sept. 8, 1983.

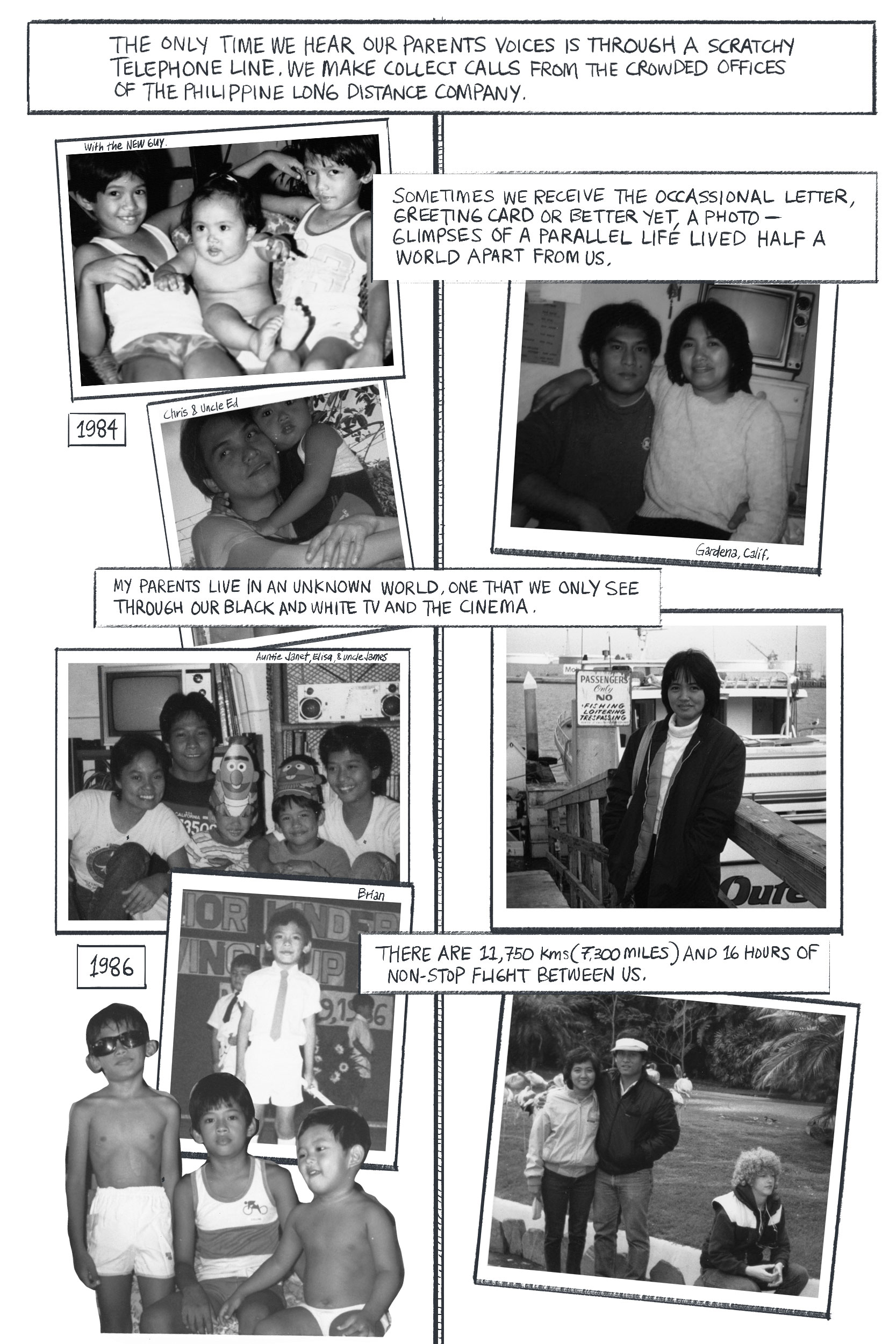

My mother arrived in Los Angeles and my parents moved into a tiny studio apartment in Gardena, a few miles southwest of the city. They lived close to my father’s parents, who lived and worked in a nursing home. Soon, my mother applied to change her visa status from her tourist visa to become a dependent of an H-1 visa holder, my father. At that time, she was given permission to work. She started helping her in-laws at the nursing home.

My brothers and I were not allowed to join my parents until my father’s paperwork went through.

More about the immigration backlog for Filipino families and people in the US on employment visas.

In December 1989, the Immigration Nursing Relief Act (INRA) was passed into law because of a severe nursing shortage. It established a five-year pilot program to allow foreign-educated nurses to enter the country on H-1A visas, the first subcategory of the H-1 visa for a specific set of high-skilled workers. Most of the thousands of foreign-born nurses who came to the US through the program were from the Philippines, and many were allowed to adjust to legal permanent resident status before the program was phased out in 1995.

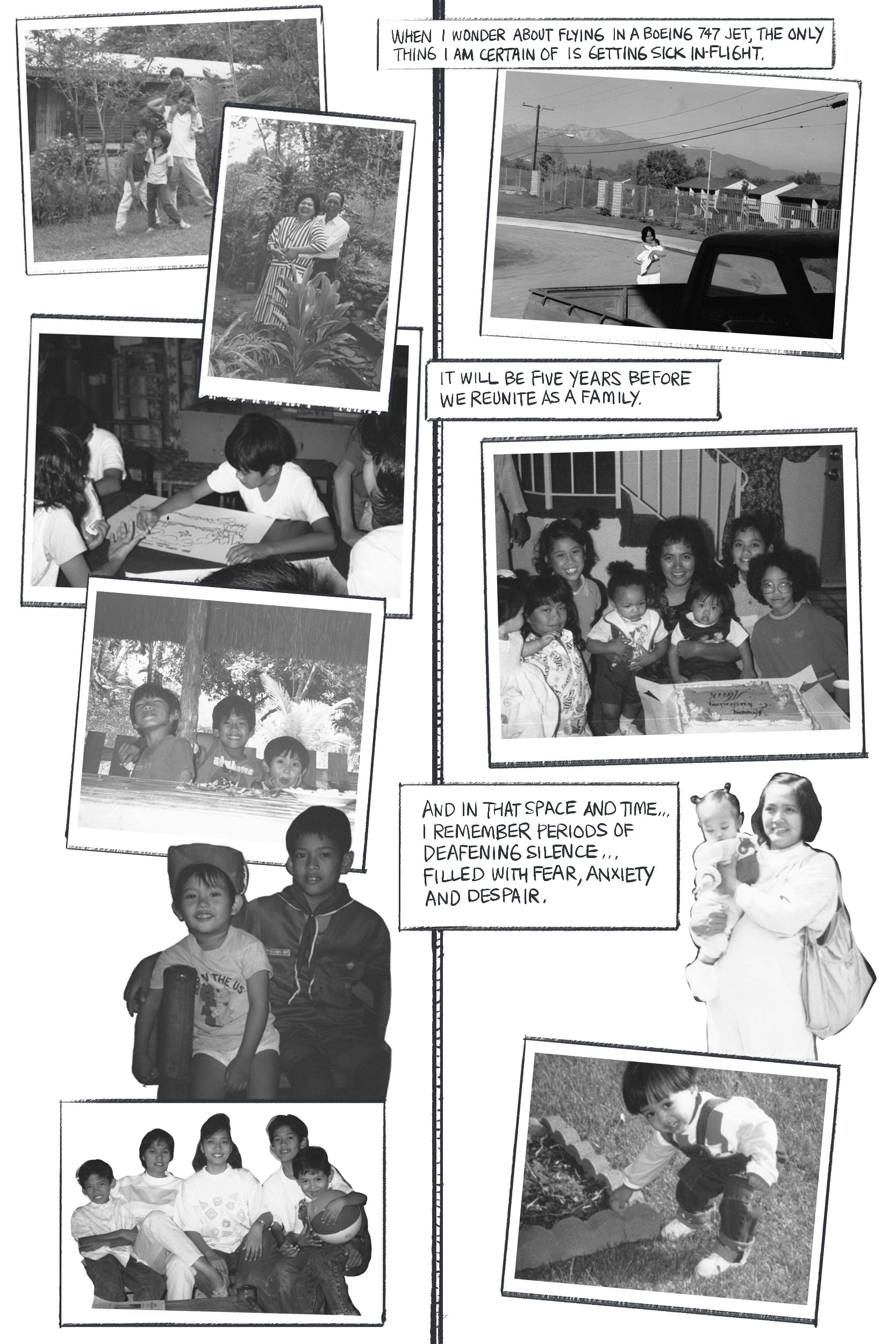

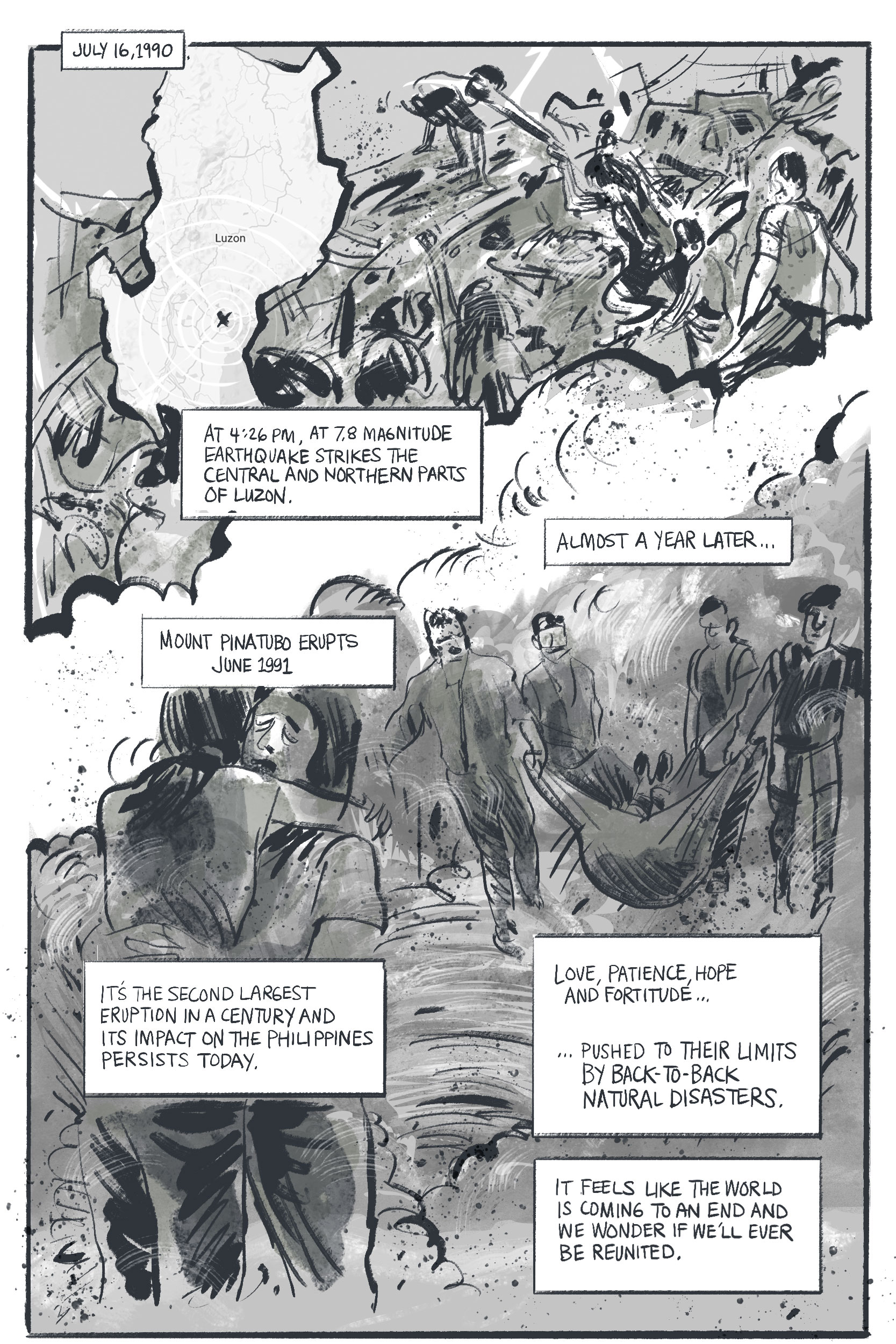

In January 1990, my parents bought their first home in Riverside, California. It was four years since they submitted their petition for legal permanent residence. My dad was a nurse, but he came to the US before INRA. They thought that INRA applications were being given priority over theirs. Their attorney in Los Angeles had no updates on the status of their petition. They considered re-applying into the INRA program but decided to hold their place in line — wherever that was — instead.

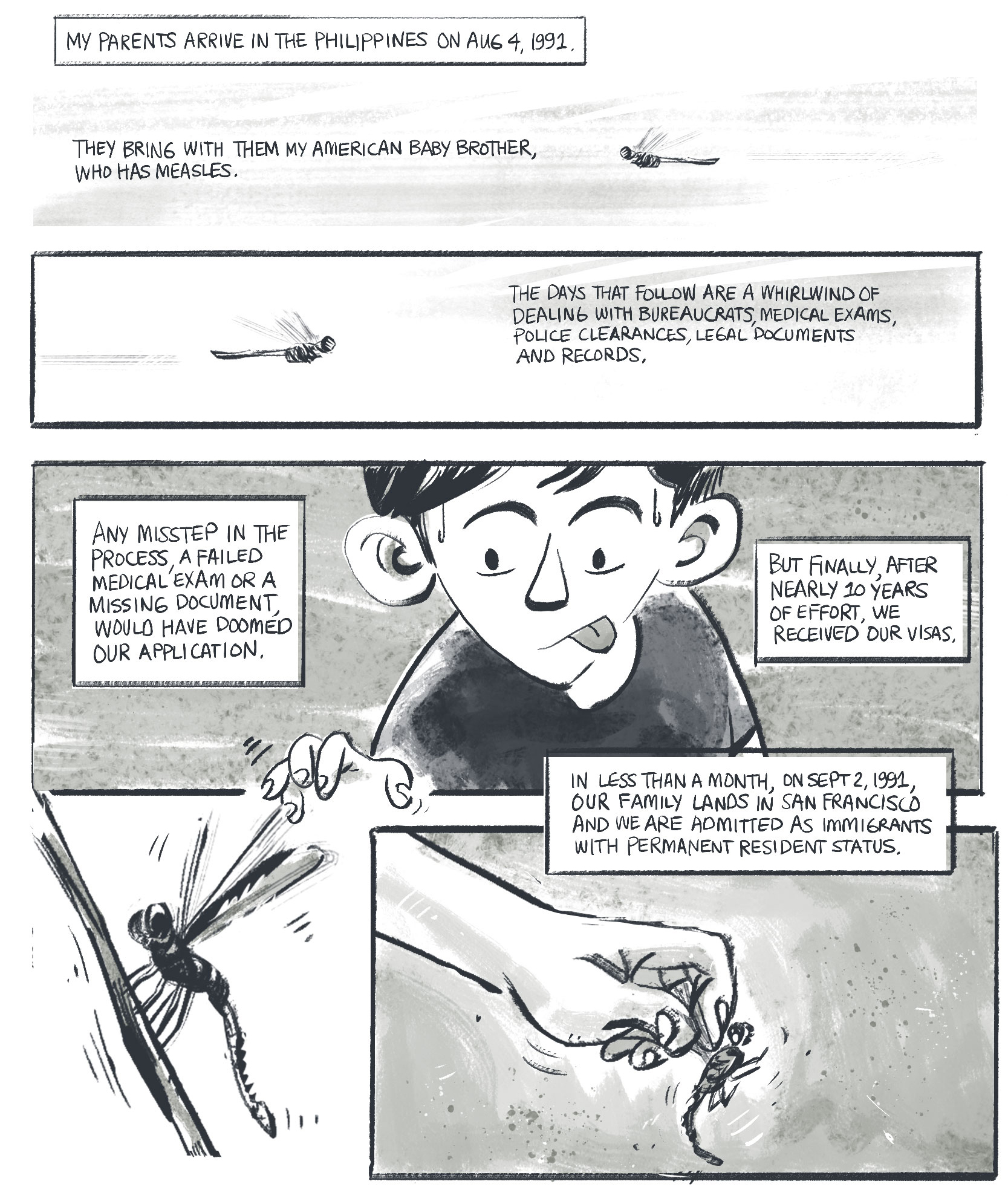

My parents did not have many avenues left to reunite my family other than to wait. They asked their congressional representative, George E. Brown, Jr., for help. He corresponded with Ambassador Nicholas Platt in Manila to inquire about the status of their petition. Platt told them that he couldn't expedite applications because they must be processed according to priority dates. He said that my father was in a queue of over 580,000 Philippine-born applicants registered for preference visas, through the sponsorship of family members or employers. But, like there is today, there was a limit on how many visas could be issued for each country. Only 20,000 were issued each year for any country, no matter how many people applied. Platt gave them a number to call to check which priority dates were being processed. (Nowadays, people check the “visa bulletin” online.) When my parents bought their house, the government was processing applications filed before May 1985. My father’s application was filed in 1986.

Today, my dad works as a dialysis nurse and my mom is a preschool director. They go on plenty of road trips and take a lot of photos, selfies in particular. My dad hasn’t gone back to the Philippines since we left in 1991.

My brother Brian, who is closest to me in age, is a Seabee US Navy veteran and works with Veterans Affairs in Syracuse, New York. He was deployed all over the world, including multiple tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. He was in bootcamp when the planes hit the towers on 9/11.

My brother Chris, who was a baby when my mother left the Philippines, is now a chef in Baltimore, Maryland. working with farm-to-table restaurants. He also served in the US Navy during the Iraq War on the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier, USS Harry S. Truman. During that time, he almost lost his arm while working on the arresting cables that catch jets as they land. He used the GI Bill to go to culinary school.

“Your brothers fought for a country that kept denying them entry back then,” my mother says.

My brother Mark, born in California, works as an IT help desk adviser in Syracuse, New York. He’s an ardent gamer and studied media arts and animation in college.

My two aunts eventually found their own ways to America and citizenship. My aunt Janet married a US airman and now works in data management in Maryland. They have two teens who come stay with us almost every summer. It reminds me of when we spent summers in Isabela with my grandparents.

My other aunt, Elisa, works as an operating room nurse in southern California. She came to the US via Canada and is now a US citizen. My parents helped her navigate the immigration and naturalization process.

My uncle, Edgar, retired in the Philippines after working as an accountant in the Middle East for an American aerospace and defense company. He came to visit the US in 2018. It was the first time we saw him in almost 30 years.

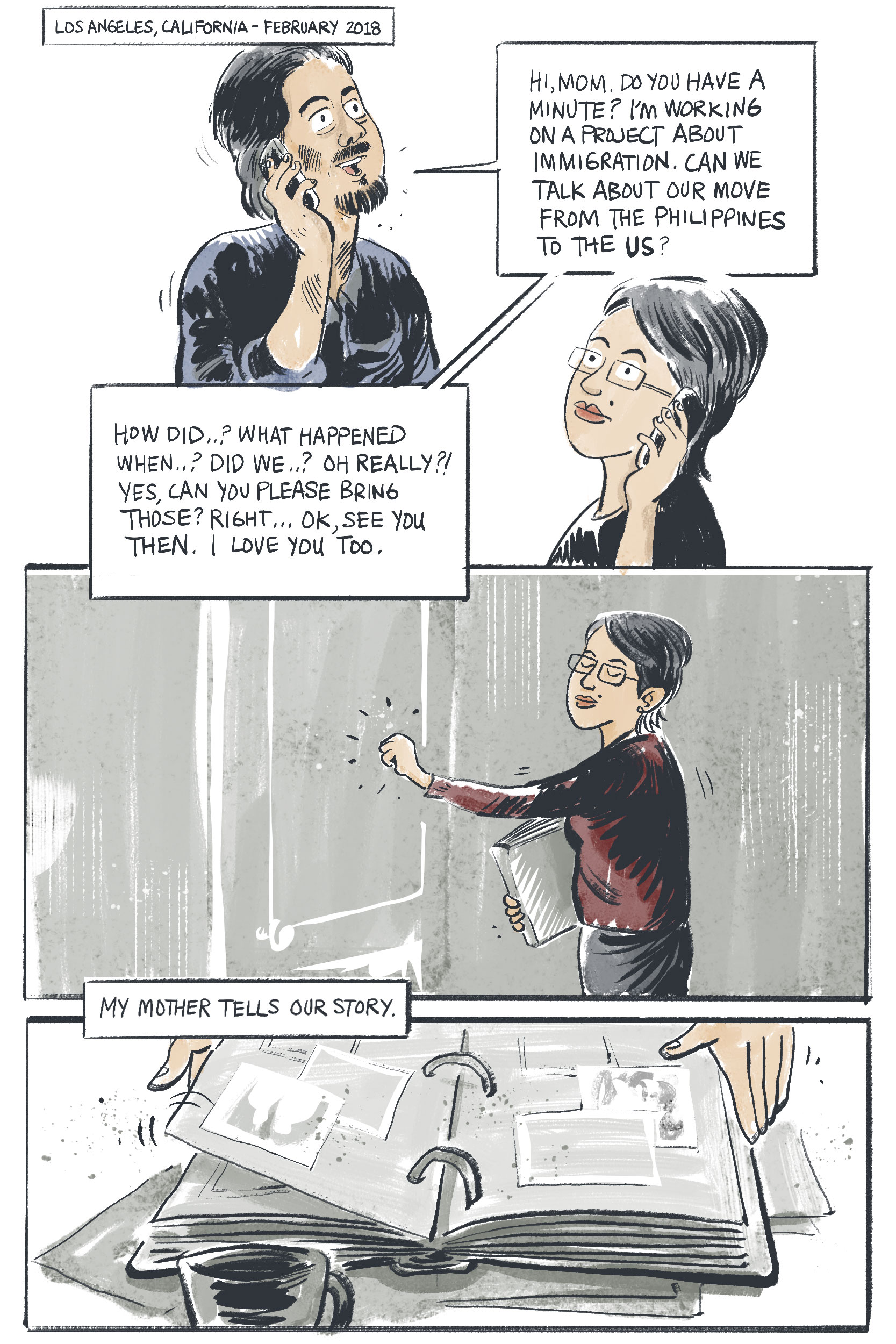

I work as a university administrator in Los Angeles while doing freelance graphic journalism. I was last in the Philippines two years ago, but I try to go back as often as I can to visit family and friends. After I went to college, I lived and worked abroad in Italy, Germany, Belgium and Japan.

I’ve been drawing other people’s immigration stories for a while. I’ve tried to use pictures to help other people understand what it’s like to be in the US immigration system.

See more of Dan's art: Follow the journeys of people trying to come or stay in the US. What choices would you make?

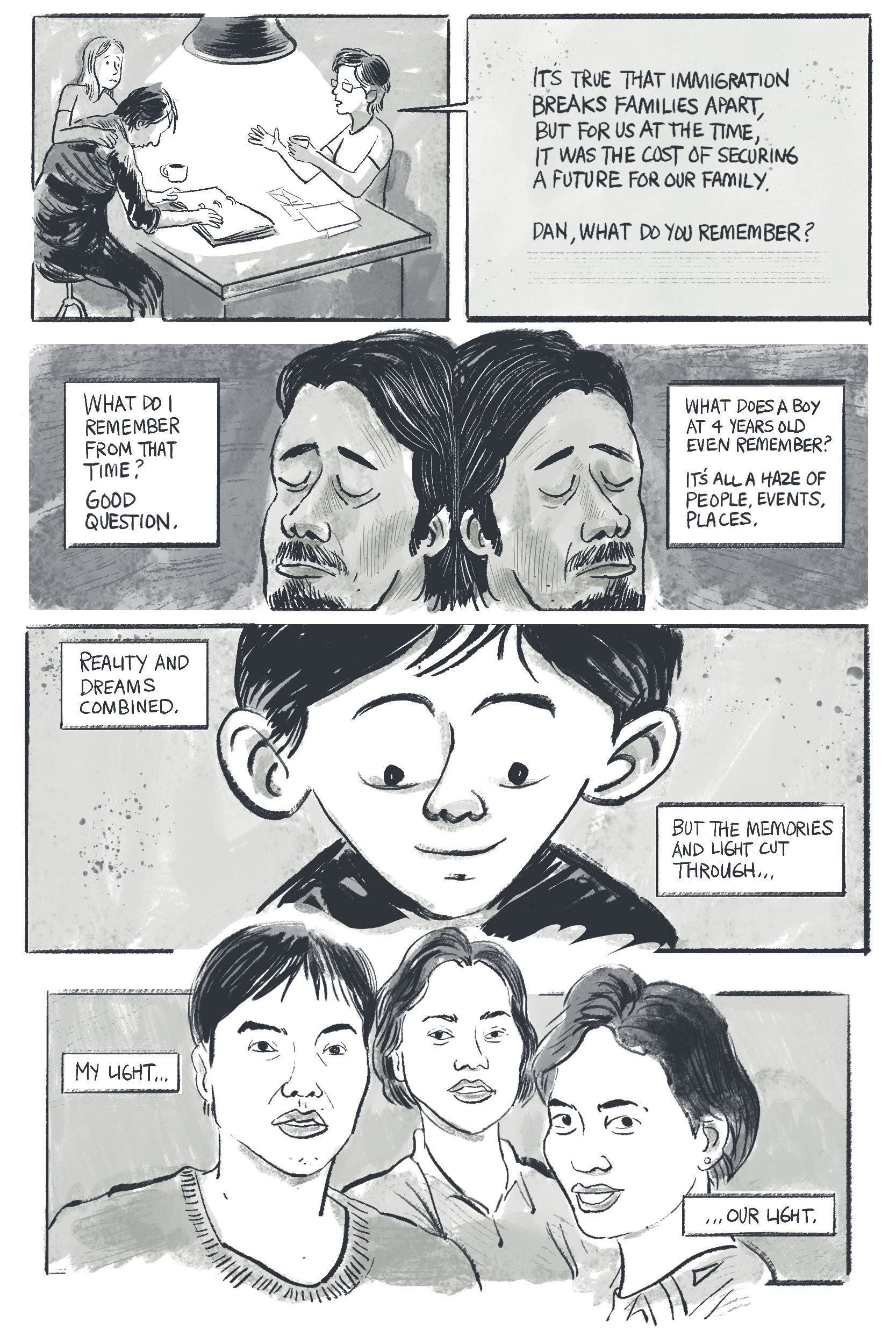

Through that work, I found myself unexpectedly transported back to my family’s own immigration and reunification story. I thought back to a time when my parents couldn’t be there for birthdays and school functions. Meanwhile, through spotty phone conversations and the pictures they sent us, we saw my parents slowly building their lives — a new house, a new brother and all without us. It didn’t make sense to me. Why did they have to leave and why couldn’t we just go with them? It felt like there was some amorphous, grand plan, but no one explained it to me and no one knew how it would all turn out. I realize now that my parents were navigating a complex immigration system that was beyond their control.

Illustrating my immigration story did not just help me look back, but it also helped me to look forward. For a long time, I felt suspended in time, plucked from a place and a life that I was living, and always waiting for that grand plan to come into fruition. Even after nearly 30 years in the US, I never went through the naturalization process. I think some part of me thought I would move back to my home country. And I’ve tried to cling as much as I could to a place that still felt like home — even returning to the Philippines every year for awhile. But slowly, over the years, I’ve realized that I’ve changed, both countries have changed, and life has moved on. Later this year, I’ll be applying to be a US citizen.

My parents took a chance in coming to the US. But we’re all together now and I know that was always the grand plan.