In 2008, the allure of coming to the United States seemed like a two-way street for Chinmoyee Datta. The US would get a qualified teacher in a district that couldn’t find enough instructors and Datta would get to experience an entirely new country.

Kolkata-born Datta had been teaching at a Catholic school in a large and growing education hub in central India, the city of Jabalpur, for 11 years. Her husband was a principal at a government school. Like her, he had job stability and credibility in his profession. Their son would soon be in fourth grade.

After attending a seminar in Delhi about the cultural exchange program and discussing it further with her family, Datta decided to apply. She didn’t think too deeply about employment visas or green cards, or what it would mean for her as an Indian citizen to make a new life in America. She had no idea she would become one of tens of thousands of Indian nationals in the US on H-1B visas waiting for legal permanent residency, or that her son would face his own decisions about what path he would take to stay in the country that would become his home.

The idea of seeing a new part of the world seduced her. It’s only a few years, she thought. Her brother-in-law in Texas, who first brought up the idea of teaching abroad, helped her file paperwork with a private recruitment company and took care of all the fees. A superintendent at an interested school district in Mississippi soon interviewed her on the phone. His questions rolled out in southern drawl, a kind of English Datta had never heard before: What are your strengths and weaknesses? How will you approach cultural differences? Given their backgrounds, do you believe the kids can learn?

She won over the superintendent. He offered her a position teaching middle school math at Durant Public School District, in Mississippi. Datta had never heard of the place, but if she needed to, she could call on her brother-in-law for help. She accepted the position. She applied for a J-1 visa for long-term cultural exchange visits, submitted the necessary fees and prepped for her pending arrival to Jackson, Mississippi, about 65 miles away from where she would live.

Her husband and son decided to follow, a year later. Datta’s father, curious about his daughter’s future whereabouts, searched all over Kolkata for a map of Mississippi. He eventually found one and saw, with satisfaction, that Durant appeared to be a big city.

It turned out the map was misleading.

Durant Public School is the only school in Durant Public School District, which serves most of the town of Durant and its dwindling population of just under 3,000. The wide, white building sits next door to the school’s central office, which the superintendent, with only a trace of tease, says is the town’s main point of interest. Past the brown front lawn and across the street, a trailer advertises itself as the Parent Resource Center. Recent rains have left stains on the front, but the trailer looks relatively new and well-kept compared to the homes on the surrounding streets. Overgrown weeds sprout from the front lawns of more than a few of the neighborhood houses.

Students trickle into the school building on a Monday morning in January. They trudge down the dim hall, past a handful of printouts affixed to the wall congratulating seniors for admissions to Jackson State University, Mississippi State University and the University of Southern Mississippi. The students wear khaki pants, boots and several layers to shield themselves from the winter chill, — items mostly purchased from outside of town given the only store nearby is a Family Dollar. Only a few students carry backpacks.

Inside a door decorated with snowflakes, snowman cutouts and a sky-blue border dotted with more smiling snowman heads, Datta’s classroom is bright and welcoming. Now 48, she has been a teacher at Durant for nearly 10 years. Her wavy, shoulder-length black hair stays put whenever she swivels her head to address one of her students.

She admonishes a student taller than her when he doesn’t show his work on the board while simplifying addition and subtraction functions. The other students duck their heads low, problem-solving and checking their math with calculators they picked up from a caddy hanging on the front wall. Ms. Datta, as she is known at school, walks the aisles of paired desks and advises the students, 12 of them in that morning’s class. “You put the negative sign here, the minus.”

A scuffle breaks out near a window. “M’Datta, you got a spider up in here!” It’s taken refuge on the windowsill and attracts an audience. Datta walks swiftly to grab some tissue and with the sweep of an arm, puts the arachnid, and the commotion, to rest.

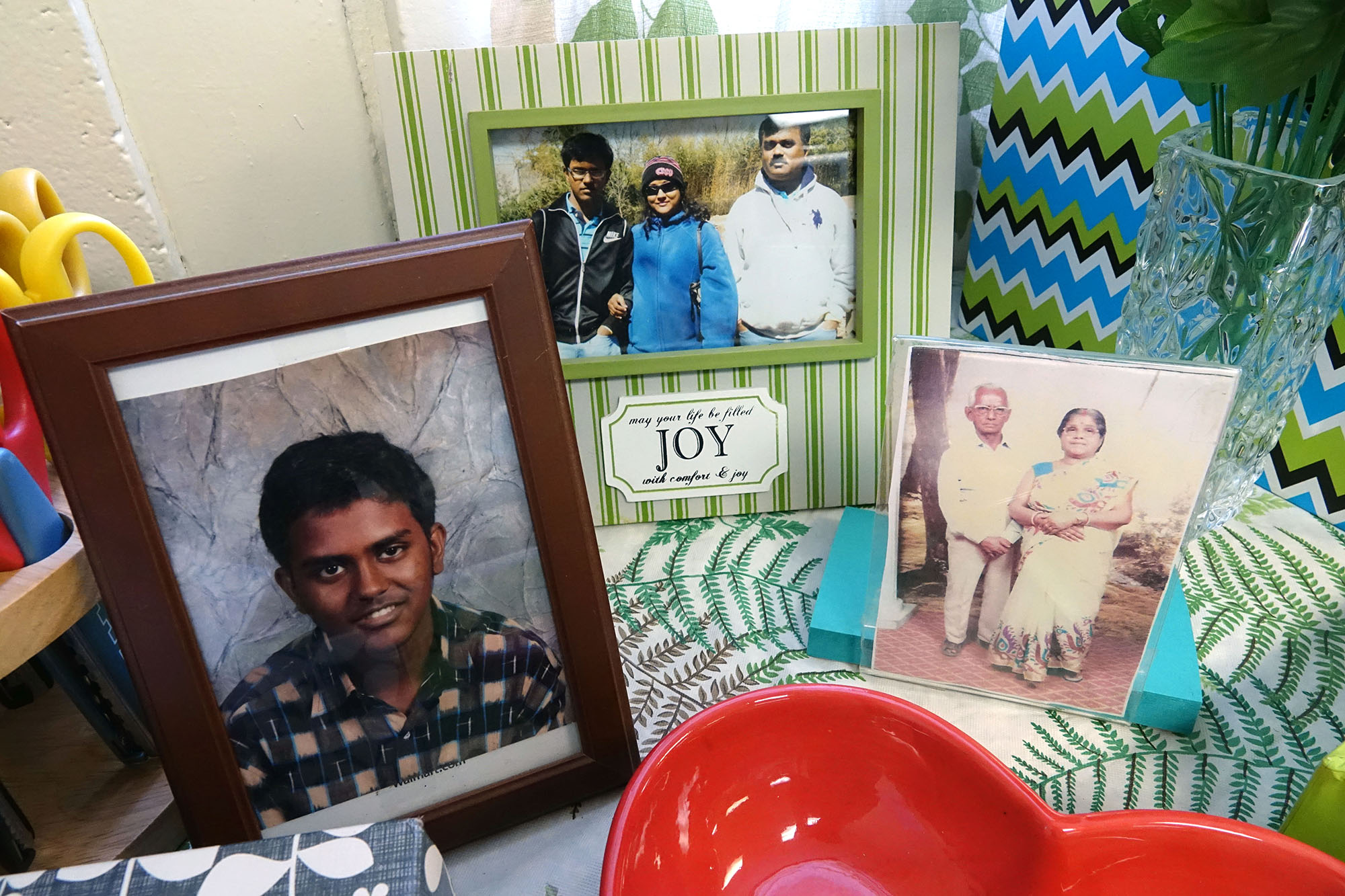

In the back corner of the classroom, a mahogany-framed photo of her son when he was her students’ age, just 13, rests on her desk next to two big binders. They contain her lesson plans, worksheets, schedules, special activities and the teaching standards of her school.

Datta didn’t anticipate she would switch her J-1 cultural exchange visa to an H-1B skilled worker visa and build a life in America. Nor did she foresee that her family would be caught up in the inflamed politics of immigration. Most of her students, and even her colleagues, don’t realize the Dattas lack the rights of citizens or permanent residents. The same is true of her neighbors in the town of Kosciusko, 20 minutes away from the school, where her family bought a home last year.

Datta doesn’t expect people would know — she’s among just 2 percent of Mississippi’s population who were born outside the US, a third of whom are now US citizens, according to the American Immigration Council.

Durant is in Holmes County, Mississippi, one of the last counties to resist school integration after Brown v. Board of Education. The 1954 Supreme Court decision declared separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional. When Holmes county was ordered to end segregation in 1969, Durant, originally a part of Holmes County School District, branched off to become its own school district.

“The white response was basically — they just left the public schools and said, we’ll just create our own private schools,” says Charles C. Bolton, a historian of Mississippi at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

That was the Durant school district.

Over time, what was a predominantly white town turned into a predominantly black town as people moved to the schools of their choice, and those with means left town. Along the way, a Nissan plant left, the textile industry shut down, a railroad stopped running and companies that build mobile homes scaled back. With the jobs, many of the taxpayers left too.

Now, more than 40 percent of people in Holmes County live below the poverty line and working adults make on average about $12,000 per year. The state has ordered the Durant Public School District to combine with Holmes County School District once more, starting July 1, to help cut administrative costs.

For now, nearly all of Durant’s students — one exception is one eighth-grader with a high-top brunette ponytail and a broad smile — are black. The number of students hovers around 500, considering irregular attendance caused by disciplinary issues or parents’ shifting employment. All of the students are served breakfast and lunch at no charge. That Monday in January, lunch is pizza and steamed broccoli, with a fruit cocktail most students don’t put on their styrofoam trays.

The cafeteria serves students in shifts, class by class, for lunch. The room is chilly, so Datta wears her sand-colored coat to supervise the students.

“What happened now?” she asks a boy who tripped on another student’s protruding foot. Laughs abound. “Finish your lunch!” she calls out.

She meanders through the small space. The students have 15 minutes to eat before the next wave of students filter in. Datta eats her lunch by herself in her classroom during the last period of the day, her prep period, she says, slightly embarrassed. Her smile reveals a gap between her two front teeth.

Life in Durant and Kosciusko was a culture shock when she first arrived, Datta says. She wasn’t used to the slow pace and the black vs. white racial divides that remain, even if people are friendly enough in passing. She had to adjust to the way some students try to run the classroom; many of them turn into mini-adults at home, caring for siblings and shouldering responsibilities in single-parent, absent-parent and grandparent-led households. Most people assumed Datta and her friend, Vinitha Devaraj, an English teacher from Hyderabad who was her roommate their first year, were Muslim, Mexican or in the US illegally — identities that raise eyebrows.

Kosciusko, famous for being Oprah’s birthplace, lies in Attala County. While some Democrats hope for an Oprah 2020 presidential bid, Attala went for Donald Trump in the 2016 election.

Still, the opportunity to make a difference as a teacher, even as a wary foreigner, was enormous. Durant had continuously advertised for teachers in local and state papers, at job fairs and at university career days. But few qualified teachers applied to work in a town where the largest storefront — in 2008 and still today — is a boarded up Piggly Wiggly.

“We couldn’t attract folks to come,” says Glen Carlisle, the school superintendent. “The shortage of teachers is so great that even after offering $4,000 salary bonuses, we’re unable to attract teachers.”

That’s when foreign teacher agencies, replicating nursing recruitment programs that specialize in sending Filipino nurses to the US, started to contact him and others with the same problem. Every single state began the 2017-2018 academic year short on teachers, according to the Department of Education, especially in math, science and education. In Mississippi, the lack of qualified teachers is especially acute in the Delta region, which includes Holmes County.

The shortage does not appear to be going away. A 2016 report by the Learning Policy Institute found a 35 percent decrease in the number of people studying to become teachers between 2009 and 2014. Twenty percent of Durant’s current teaching staff is uncertified, Carlisle says.

“Have you seen the need for teachers in this country?” It’s more of a statement than a question for Anita Gupta. She manages USA Employment’s Teach in America program for international educators that, similar to the non-profit Teach for America, places teachers in schools across the US. It’s the program that facilitated Chinmoyee’s hiring.

“I bring only 50 teachers a year, which is only a drop in the bucket,” says Gupta.

But overall, international teachers come to the US in relatively high numbers, says Lora Bartlett, an associate professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and author of “Migrant Teachers: How American Schools Import Labor.” Over a 10-year period Bartlett studied, from 2002 to 2012, more than 100,000 foreign workers came to teach in US schools.

Most teachers come from the Philippines, India, Mexico and Spain, she says. They typically arrive with a J-1 cultural exchange visa, because it’s more flexible than the H-1B skilled worker visa. But they often end up in the latter visa category if they decide to stay longer than the J visa allows, usually two to three years.

“It’s pretty hidden because they’re teaching the lowest-income, highest-need urban and rural students in the country,” says Bartlett.

When contract renewals came up toward the end of her first academic year at Durant in the spring of 2009, Datta was not surprised she was made an offer to stay. Her friend, Devaraj, felt the same way. After all, their students’ test scores had shot up, and the two women knew they excelled at teaching. They were also certified by the state.

The looks on some of their colleagues’ faces, though, revealed that not everyone was invited to stay. That was the first and last time Datta and Devaraj felt tensions with their colleagues from being foreign workers in America.

Datta’s husband and son soon joined her in the US on J-2 visas, as dependents of a J-1 visa holder. Her husband, Mihir, a disciplined man with excellent posture and a professorial air, easily found a job teaching high school math, chemistry and physics at Durant. He was relieved his visa allowed him to work.

“I am a principal in India for 20 years,” he says. “I cannot not work.”

Carlisle, the superintendent, was relieved too. He admired the work ethic of his three international teachers, and the exposure to new cultures their presence brought the students. In 2010, he urged them to stay in Durant and switch their expiring J visas to employee-sponsored H-1B visas so they could continue to teach at the school. Accordingly, their children — the Dattas’ son and Devaraj’s two daughters — swapped their J-2 visas for H-4 visas, the visa for dependents of people who hold H-1B visas.

Devaraj’s husband also switched to the H-4 spousal visa, and lost his ability to work. Years later, when President Barack Obama issued an executive order granting H-1B spouses work permits, he got a job as a clerk in a gas station. The Trump administration has since proposed revoking these work permits.

During these years, life in Durant and Kosciusko was transitioning from strange to familiar for the Dattas. Mihir Datta became “Mr. Popular” among the students. He found that since they often came to school hungry, food and treats could motivate them to study.

“I say that if you get a good grade, if you bring all As, then I’m going to give you a chicken on stick,” he says, referring to the chicken sold at gas stations, among the few places to eat out in Durant.

Some of the students who once asked Ms. Datta about the sindoor she wears in the part of her hair became teachers to other inquisitive students, explaining to them that the red powder is a sign of marriage. After trying her sweet, Nescafé-fueled, milky coffee, her colleagues started to sneak little cartons of milk to Datta, with notes: “Will you make me some Indian coffee too?” Rather than nurturing grudges, a few of the teachers who weren’t given contract renewals turned to the Indian teachers for help passing state teacher certification exams.

Meanwhile, the Dattas’ son Mayukh went from fielding jokes about being related to Osama bin Laden to figuring out the perfect way to explain the faded, red thread bracelets he wears on his right wrist. He’s asked about them almost daily. He compares wearing it as part of his Hindu faith to the way Christians wear crosses.

“Because that’s something they get, right?” he says.

Mayukh, who recently turned 19, is a bright and conscientious college student who thinks before he speaks and debates which of his interests should become his passions. On top of Durant’s obvious need for teachers, Mayukh's future is what inspired the Dattas to consider Carlisle’s offer to stay more seriously. As teachers, they know full well the pains ambitious students in India take to get into top-tier colleges — after-school classes and non-stop studying, accompanied by high stress and a rising rate of suicide among students. They didn’t want that pressure and competition for their son.

The teachers and administrative staff at Durant held a meeting to make a plan for their teachers to stay. Whatever their feelings about immigration policies, their decision was obvious and unanimous: Apply for the teachers’ green cards, which would give them permanent residency in the United States.

“Our need was so great, there was absolutely no pushback,” says Carlisle. “Absolutely no pushback now.”

That was in 2012.

“My problem right now is my son’s problem,” says Chinmoyee.

It started when Mayukh began to look into college applications his junior year of high school. A family friend told Mayukh he would have to transition to an F-1 student visa, for international students. Otherwise, Mayukh wouldn’t be able to work or intern while in school. And when he turns 21, he won’t be able to keep his H-4 visa at all — meaning without a new visa, he’d have to leave the US or become undocumented.

The Dattas were confused. Mayukh has been in the US since fifth grade. They paid taxes. Even though they were in a long line for their green cards, US Citizenship and Immigration Services approved their I-140s, their employer’s petition for them to work in the US permanently.

Mayukh revealed his immigration status to his high school counselor. He was attending the Mississippi School of Mathematics and Science, a public magnet school for academically-motivated high school juniors and seniors. The school, housed at the Mississippi University for Women, accepts students who are residents of Mississippi. It’s a residential school; the students all live on campus together while they study.

Mayukh had to explain the significance of the H-4 visa — that it means Mayukh isn’t a legal permanent resident. “Because obviously he didn’t know,” Mayukh says. “Because I was — I think I was the very first one, or maybe the second student, to really kind of have to go through this process.”

The counselor told Mayukh that he wasn't eligible to file the FAFSA, the application for federal student aid, or apply for most scholarships, which require citizenship or permanent residency. His heart sank.

Then, during a visit to Tufts University, other hurdles pricked his nerves. Mayukh says a counselor he met there was honest — brutally so. Tufts, in the Boston area of Massachusetts, is out-of-state for Mayukh, so they would consider him an international student. His parents earn Mississippi teacher salaries of around $50,000 a year — which would have qualified Mayukh for more need-based scholarship opportunities to afford the $50,000-a-year tuition if he weren’t considered an international student.

Ever the optimist, Mayukh applied anyway. He was rejected — he believes in part because the university considered that he might not be able to pay the tuition.

Tufts University declined to comment, citing university policy, but that a “fairly small and highly qualified group of international students” are offered financial aid, based on need and qualifications. That Mayukh is in line for a green card doesn’t matter.

A looming lose-lose situation started to weigh on the Dattas. If their son were to enroll at an out-of-state school — which he wanted to, given the quality of many schools outside of Mississippi — he would likely be admitted as an international student, facing fees and charges they could not afford unless the schools also offered generous financial aid packages.

Even if Mayukh went to an in-state school, with in-state tuition, he would have to transition from his H-4 dependent visa to an F-1 student visa before he turned 21, or sooner if he wanted to work. Whichever path he chooses, if he turns 21 without receiving a green card through his parents, who have already been waiting six years, he will start down his own path to permanent residency. If Mayukh opted to return to India — an option he doesn’t even want to think about — the culture and educational shock could be enormous. Plus, going back to India would separate him from his parents.

In the last few months, the Trump administration introduced, and then backed away from, a proposal to stop H-1B renewals for people like the Dattas, even if they are in line for their green cards. The proposals have given the Dattas something else to worry about. If the H-1B program is curbed, they might all be forced to go back to India. That would be a challenge for them, but also for their other kids: the students at Durant.

The conundrum is now a daily conversation for the family.

Educational employees comprise a tiny minority — just 2.5 percent, according to the Department of Labor (PDF) — of those who are considered “skilled workers” in the H-1B program. Most H-1B visa holders work in IT or technology. They can also be doctors, academic scholars, religious workers, executives or healthcare aides. The salaries for H-1B visa holders are based on wage surveys of both occupation and location. An IT worker in Silicon Valley, for example, earns more than a teacher in the Delta.

Yet both, if they apply, fall in the same green card category lines. There are five types of green cards for H-1B workers, distinguished by work and ability; most applicants are in the second and third categories for people with advanced degrees and who can do high-skilled work. Still, it’s not a person’s occupation that dictates wait times and approvals within each category, but country of origin.

And so, a hurricane hovers over one particular group in the US with H-1B visas. People from India.

Here’s the math: 70 percent of people on H-1B visas are from India, which means Indians apply for the most green cards, by far. The US issues about a million green cards a year, 140,000 of which are employment-based. Each country has a limit of how many people can get these green cards, seven percent of the total number issued a year — regardless of a country’s population or how many people applied. So USCIS, as of February 2018, is still reviewing Indian applicants who filed their paperwork for employment-based green cards in 2008 and 2009. People from China also wait a long time: some who are current under review filed their paperwork in 2008, while in other categories they filed in 2014 and 2016.

Durant Public School first filed paperwork for the Dattas’ green cards in 2012.

The government is 10 years away from clearing the existing green card backlog for Indian nationals, whose wait time keeps rising. David Bier, an immigration policy analyst at the libertarian think-tank Cato Institute, has written about the decades-long wait some Indian immigrants face for legal permanent residency. An advocacy group, Skilled Immigrants in America, estimates that with the number of people being added to the queue every year, the wait time could eventually increase to 70 years.

As a result, Indians are waiting for their green cards for so long that some of their children are no longer children.

Two dozen Indians on H-1B and H-4 visas told PRI about how the green card backlog affects them. While one person said she did not intend to stay in the US long-term anyway, most expressed dismay at their situation and doubts about their futures.

Prasanna Dharmadhikari in Cupertino, California, says his son turned 20 on New Year’s Eve. “People look forward to becoming 21, right? For him, it’s a big question mark,” he says.

“What is the solution? I don’t know, I just pray to God,” says Asha Gopisetty, a teacher in South Carolina. Her daughter came to the US at age 7 and just turned 20. “She is neither Indian nor American.”

A father in Chicago, Vimochan Cheethirala, feels there is no way his son, who came to the US when he was 7 months old and is now 12, can adjust to India if he has to return. “So I’ve been exploring the opportunity for him to immigrate to Canada,” he says. “I’ve actually hired an attorney and did the preliminary requirements.”

Meanwhile, Nishikant Kherdekar, a father-to-be in Dublin, California — who came to the US on an H-4 dependent visa, transitioned to an F-1 student visa, and is now on his own H-1B professional visa — says the visa headache is not worth it.

“I have been hoping for a change for the last 16 years and I have been going through this situation. But it is just beyond my patience anymore,” he says. His child will be born a US citizen, but he anticipates that the family will still leave. “There is no point in staying here for another 18 years in such a limbo situation where you are just one layoff away from losing everything that you’ve worked toward building.”

A few congressional bills are trying to reduce the backlog by increasing or abolishing country quotas. One bill in the House, HR 392, would remove per-country caps for employment-based visas. The advocacy group Immigration Voice also proposes that Indians in the green card backlog pay higher fees to speed up the process — revenue which the government would be free to use in whichever way it wants, including to help pay for Trump’s expansion of the wall on the southern border.

“The Indian high-skilled workers will gladly, enthusiastically and happily pay for the wall if given the opportunity to do so in order to get fair treatment on green card waiting times,” Leon Fresco, an attorney for Immigration Voice, told McClatchy News in January 2018.

While lawmakers push for a bipartisan immigration plan and Trump continues to push for a “merit-based” immigration system, critics say that if HR 392 passes, it would fundamentally alter the diversity of people who come to the US. It would become, as Center for Immigration Studies fellow John Miano wrote, an "India-first policy.”

Still, Robin Savinar, a PhD candidate at the University of California, Davis, who researches how the H-1B visa program affects workers, notes that citizens from countries like England and Canada have a far different experience with the green card system than Indians and Chinese people, despite sharing similar qualifications and expertise.

“The difference is that the wait time for those workers is so much shorter than it is for workers from India and China,” she says. That’s why some people argue that America’s immigration policy is discriminatory — because it amounts to different experiences for different people.

“The law in itself as it’s written is benign, seemingly, but in many cases, racism now takes that form,” says Savinar. “If the results are different for one group than another” — she pauses, choosing her words carefully — “in fact, it could be considered ... perhaps a racist policy.”

From 2006 to 2016, the US issued 678,746 H-4 dependent visas to Indian nationals, according to the State Department. Pallavi Banerjee is a sociologist at the University of Calgary who is writing a book about the experiences of H-4 and H-1B visa holders. Her estimate, based on her research, is that about 10 percent of those visa holders are children.

But she does not have precise numbers — nuanced data on children of H-1B visa holders is hard to come by — and that, along with the fear of speaking out among many Indians, has kept the stories of these children relatively unreported. Indians often talk about their circumstances on WhatsApp or in private Facebook groups. Most public activism around the H-4 visa has so far focused on dependent spouses. Now that their children are turning 21, she says, more people are willing to open up.

“My other informed hunch is that we still are not hearing as much as we should, probably,” says Banerjee.

Some activists have started to refer to their children as “H-4 Dreamers,” borrowing from another immigration movement. The Dream Act, first introduced in 2001, proposed a path to citizenship for some undocumented immigrants who were brought to the US as children. It was the precursor to the DACA program, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which so dominates the politics around immigration today.

Hearing that Indians face similar struggles creates a new narrative for the community, says Banerjee. Indians in the US, especially temporary workers, tend to want to maintain their status as a “model minority” — which creates distances between communities and hierarchies of deserving immigrants.

The H-1B and H-4 visa holders who spoke to PRI say they support DACA, but that they too deserve relief: We pay taxes. We are contributing to the economy. We came here legally. Our children came here legally. Yet everyone knows about DACA and no one knows about us.

There is an opportunity for joint advocacy between different “Dreamers,” Banerjee says, but it will depend on how much Indian nationals want to engage with other groups and bust model minority myths.

“The umbrella term of the ‘Dreamers’ has the potential to create solidarities across minoritized immigrant groups and their struggles,” she says. “If such an effort is not made by the ‘H-4 Dreamers,’ then it becomes coaptation and appropriation of a political struggle that has a longer history of resisting harsher forms of racialized oppression.”

For the Dattas, Indian immigrants’ advocacy sometimes leave them out too.

On a cool Friday evening, they open the door to their house with welcoming smiles but a muted panic. The Trump administration had just proposed curbing H-1B renewals, even if those visa holders are in the green card queue. That would effectively force many Indians who have been in the US for years to leave.

“We are being put in the same category as the IT sector who are living in Silicon City or some other places,” Mihir says. His bushy eyebrows furrow. He wishes teachers could just have their own specialty green card category.

The Dattas live in a modest, one-level home with a sloping driveway in a middle-class neighborhood of Kosciusko. The books of Rabindranath Tagore, India’s first Nobel Laureate, line a TV stand that also includes photos of Mayukh when he was a baby and in middle school.

Devaraj and her older daughter, Gitanjali, who will age out of her H-4 status in a year, join the Dattas for dinner. Before they eat, as they often do, they vent their visa woes.

Devaraj worries about being a single breadwinner trying to put two children through college on a teacher’s salary if the government takes away her husband’s work permit.

“If he can’t work, it’ll be hard for me,” Devaraj says. Her voice is glum.

Chinmoyee imagines other scenarios. What if they had transferred to the H-1B visa sooner and started the green card process sooner? Could they have beaten the backlog? Or what if they knew about the backlog when they were still in India?

“Hindsight is always 20/20,” Mayukh adds, with a rueful smile.

Their neighbors and colleagues ask them what they think of the election of Donald Trump. They reply that they can’t vote — and they leave the conversation at that. Explaining their immigration status is more convoluted than most people, including other Indians, have the patience to understand.

“I think there’s no unity,” Devaraj says. “I feel that.”

The owners of Kosciusko’s three motels are all Indian, the teachers say, but they came to the US in the 1990s, before the backlog was so long. Indians who live in wealthier states like California may deal with a higher cost of living, but California has some of the best schools in the country. Navigating options for education and in-state versus out-of-state tuition for children on H-4 visas doesn’t seem as complicated for them, Chinmoyee says.

Plus, coastal Indian immigrants have strength in numbers, she adds, remembering a gathering at her cousin’s place in New York.

“It was filled like that, all Indian community over there,” says Chinmoyee. “They’re talking to each other about all those kind of immigration problems. But here, all the way in the South in this small city — we just talk to each other. And there is nothing we can do.”

She and Devaraj laugh. They complain only to each other, mirror images desperate for a way out. But they’re not interested in wrapping themselves up with the politics.

“I’m 48 and I’m having my high blood pressure from when I was 32,” says Chinmoyee. “So I just want to stay my life peacefully.”

The conversation turns toward the activism of H-1B holders, mostly in tech, who are strategizing social media campaigns and traveling to Washington to meet with lawmakers. Chinmoyee and Devaraj exchange a sideways glance and chuckle.

“They are going to do anything separately for the teacher?” asks Chinmoyee.

“We are putting our full effort into raising American kids,” she says. “We just need a little bit of help for our kids, too.”

On a moody Sunday afternoon that threatens rain, the Dattas pile into their gray Toyota minivan. A laundry basket and cardboard boxes of food, binders and books sit in the trunk.

Mihir expertly maneuvers the van across one of Kosciusko’s main drags and onto a two-lane highway, bordered by leafless trees and vast stretches of farmland.

“Mississippi backroads,” Mayukh says with a grin.

It’s the last day of winter vacation. The second semester of his first year at Mississippi State University starts the next day. Mayukh decided to attend the school after he was awarded a full ride to cover the in-state tuition, and another scholarship that covers room and board. Not having to worry about that money leaves his mind to consider another strategy.

As they caravan down the tunnel of trees and pass a town famous for having five churches and a stop sign, Mayukh talks about choosing his major. This will help determine what he should study in graduate school, which will in turn help him get a job that includes employer sponsorship for an H-1B visa — but it must not be a job that will place him in one of the backlogged green card categories. He must qualify for the category that major technology firms refer to when they talk of immigrants spurring innovation in America: the first green card category, sometimes called the “genius” category.

So, after lingering on political science, psychology and educational policy, Mayukh has decided to study renewable energy.

“It’s very much a shot in the dark. This future I’m imagining for myself may not be possible,” he admits. “Because you need a permanent residency or a citizenship.”

He fiddles with his Apple watch, a graduation gift from his parents, and his phone, which contains pictures of his best group of guy friends from high school, posing as a posse in front of railroad tracks. They look like they could be boy band photos or advertisements for diversity. A few in the group go to elite universities and want Mayukh to transfer to a more competitive school as well. Mayukh thought about it over the winter break. He’s not that interested; he doesn’t want to lose focus on his classes at Mississippi State.

Thinking about his friends puts his own life in perspective, he says. There’s the friend who was abused by his biological father. The one who is always overshadowed by his older brother. The one who now goes to a great school but whose poverty-stricken home life shocked Mayukh when he visited for the first time over winter break.

“No one’s struggle is more important than others,” Mayukh says, staring out the window.

They park the van in front of the dorm Mississippi State University reserves for honors students. As darkness sets in, Mayukh runs in and out of the lobby, shuffling in his dorm room necessities: granola bars, Maggi noodles, Sriracha sauce, notes from his high school math courses.

Inside their dorm room, Mayukh and his mother fit his sheets on the top bunk. A painted portrait of a brown-skinned Muslim woman wearing a hijab made from the US flag is perched on the top shelf of Mayukh’s bookshelf. The artist is another Indian student who will eventually have to make the H-4 to F-1 visa transition. Mayukh filed his own application for an F-1 student visa last October.

“I know he has trouble getting internships and stuff,” says Ryan Hopson, Mayukh’s former high school suitemate and current college roommate. He doesn’t really understand all the different issues well, he says while returning Mayukh’s moving cart to the front desk.

Mr. and Ms. Datta — that’s how they often refer to each other because it’s how they talk to each other at school — decide to stop at a Starbucks near the university, a treat for themselves when they are in the area. During the hour-and-a-half drive back to Kosciusko, the rain erupts. Water runs down the windows as Mihir, between coffee sips, describes how an alumnus of Durant recently approached him at a school basketball game: Namaste! Aap kaise hain? Hello! How are you?

The two teachers laugh at the interest the students take in Hindi and Bengali, languages they usually reserve for their domestic life.

The Dattas arrive home with enough time left in the evening to plan for the next school day. They both have morning duty tomorrow. Classes start at 7:45 a.m., but the students start coming at 7:15 a.m. for the free breakfast. They aim to leave the house by 6:45 a.m.